Retinal Detachment

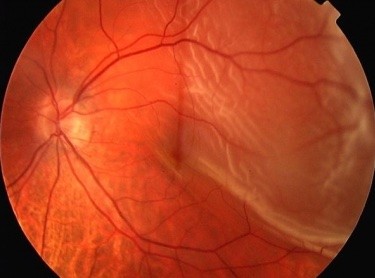

A retinal detachment occurs when the retina comes away from its normal position at the back of the eye.

Retinal detachment is a reasonably common, and treatable, cause of visual loss that affects almost 1% of the population. It must be considered when there is the sudden onset of flashes, floaters, a shadow in the peripheral field of vision, or visual loss.

The retina is a layer of neural tissue that lines the inner surface of the back of the eye. It lies on the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and its inner surface is in contact with the vitreous, which is a clear gel that fills the central cavity of the eye. The RPE is a supportive layer of cells that pumps fluid from under the retina, creating a suction force that maintains retinal attachment. The vitreous has no role in the maintenance of retinal attachment or intraocular pressure, but has an important role in the development of most retinal detachments.

The central area of the retina is the macula. In the centre of the macula, the fovea is adapted to allow vision of high acuity and colour vision.

Retinal Detachment

What is a retinal detachment?

Retinal detachment occurs when fluid from the vitreous cavity passes through a retinal break, leading to separation of the retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium. By analogy, fluid collecting behind wallpaper would cause the wallpaper to fall off the wall.

Who gets retinal detachment?

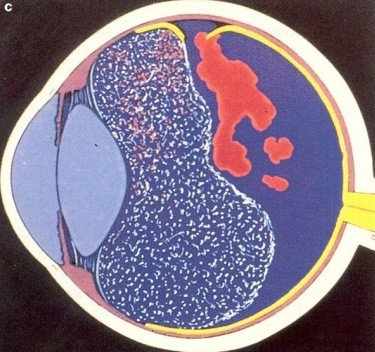

Posterior Vitreous Detachment causing retinal tear

Posterior Vitreous Detachment

With age, the vitreous degenerates and separates from its contact with the retina – this is called a ‘Posterior Vitreous Detachment’ (PVD). Development of a PVD is a normal ageing change, and is found in approximately 65% of patients over 70 years of age. It may be asymptomatic, but many patients present with the sudden onset of floaters (vitreous debris becomes visible because it is suddenly mobile with respect to the retinal surface) and flashes (if traction is exerted on the retina as the vitreous separates). The flashes are usually like sparkles or brief lightning streaks in the peripheral field of vision.

If there is an abnormally strong site of contact between the vitreous and the retinal surface, vitreous separation at the time of PVD exerts traction on the retina that may cause a retinal tear, and subsequent retinal detachment. Thus, a PVD is the usual precipitant of a retinal detachment.

Patients presenting with the sudden onset of flashes and floaters have a 15% risk of having a retinal tear. If a tear is present, there is a 40- 50% risk of developing a retinal detachment over the next 6 weeks.

Risk Factors for Retinal Detachment

Factors that increase the risk of retinal detachment include:

- increasing age,

- short-sightedness (myopia),

- some peripheral retinal abnormalities (eg ‘lattice degeneration’ of the retina, which is associated with an increased risk of developing a retinal break),

- a history of retinal detachment in one eye and a family history of retinal detachment,

trauma is a relatively uncommon cause of retinal detachment, and

cataract surgery is associated with a small risk of retinal detachment.

Symptoms of Retinal Detachment

- The sudden onset of

- flashes and

- floaters,

- loss of the peripheral visual field (a shadow in the side vision of one eye that moves towards the centre of vision), and

visual loss are the usual symptoms of retinal detachment. Flashes and floaters generally precede the onset of a shadow or vision loss, but they can sometimes be minimal and barely noticed.

When to be seen:

Sudden onset of flashes and floaters: see an ophthalmologist within a few days to confirm the diagnosis and exclude the presence of peripheral retinal tears or detachment.

If there is loss of visual field or decreased vision:

see an ophthalmologist on the same day.

Examination at retina consultants:

What to expect

A complete history of your current symptoms and your past eye problems, as well as your general medical history will be taken. Then your pupils will be dilated and a thorough eye examination performed. This will include examination at the slit lamp to confirm the presence of a posterior vitreous detachment and to examine your macula. Examination of your peripheral retina will often be performed with you lying down, to allow the best visualisation of the retina for the detection of retinal tears and detachment.

Your management will depend upon the findings of this detailed evaluation.

If a retinal tear is found, this can usually be treated immediately in the office. If a retinal detachment is present, surgery is needed.

Treatment of Retinal Tears

When a retinal tear, but no retinal detachment, is present treatment with either laser or cryotherapy is used to seal the tear before it progresses to retinal detachment. This decreases the risk of retinal detachment from 50% to approximately 4%.

Most tears can be treated with laser in the office.

Surgical Repair of Retinal Detachment

Once a retinal detachment is present, surgery is required. Without intervention, the detachment will continue to extend until the retina is completely detached causing total loss of vision.

The first step is a detailed discussion explaining retinal detachment, the need for surgery and outlining the retinal detachment operation and its timing. This is important, since a retinal detachment often comes ‘out of the blue’ and because it is a serious problem that can be associated with a degree of permanent visual loss. Also, retinal detachment surgery is a complex procedure that has important aftercare requirements.

Timing of Surgery

The most important determinant of your final vision is the extent of the retinal detachment, and your vision, when you first present. This mainly reflects whether or not the retinal detachment involves the central part of the retina (the macula).

If the central macula is not involved (‘macula on’) and vision is normal it is important to operate before the detachment extends. Generally surgery is organised for the same, or the next day.

If the central macula is involved (‘macula off’), visual acuity is decreased and the postoperative vision will never be as good as before the detachment occurred. The urgency of repair for a ‘macula off’ retinal detachment is less (since a short delay makes little difference to the final vision) and surgery is organised as soon as it is convenient, over the next few days.

The aim of surgery is to ‘close’ all retinal breaks that have caused the retina to detach. This allows the ‘RPE pump’, which removes fluid from the sub-retinal space, to restore and maintain re-attachment of the retina. There are two main surgical procedures for repair of retinal detachment. The choice of procedure depends upon the findings when you present, and is individualised for each person. Sometimes, scleral buckle surgery and vitrectomy are combined.

Today, vitrectomy surgery is the most common method of retinal detachment repair.

Surgery is carried out in hospital, safely and comfortably under ‘assisted local anaesthesia’. With this technique, you are sedated and the eye and eyelids are anaesthetised using an injection of local anaesthetic around the eyeball.

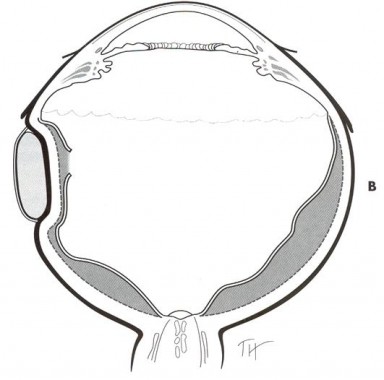

Scleral Buckle Operation

Scleral Buckle Surgery

The traditional method of retinal detachment repair is scleral buckle surgery. The operation aims to close the retinal breaks by sewing a silicone ‘buckle’ onto the sclera.

The buckle is a soft piece of silicone that has a rectangular shape. It is placed on the outside of the eye (like a belt placed around your waist) so that it creates an indentation into the eye. This indent is positioned under the retinal break, effectively ‘closing’ it. Before the buckle is tightened, cryotherapy is applied to the retinal break so that it is sealed to the underlying RPE, thus preventing re-detachment. Sometimes, reattachment of the retina is aided by draining fluid from under the retina, or injecting gas into the eye to close the retinal break internally.

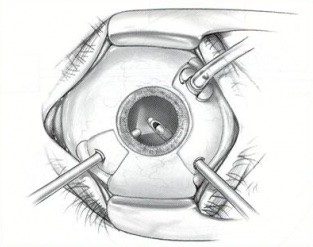

Vitrectomy Surgery for Retinal Detachment

A vitrectomy operation is a complex, modern microsurgical procedure. Most retinal detachments are now repaired using a vitrectomy procedure.

Vitrectomy procedure

During a vitrectomy procedure, small instruments (approximately the same thickness as a needle used to take blood) are placed inside the eye to remove the vitreous that fills the central cavity of the eye. This allows internal access to the retina. Retinal breaks can then be identified, and the retina reattached by infusing air into the globe whilst draining the subretinal fluid from underneath the retina. Retinal breaks are then treated with laser or cryotherapy. At the conclusion of surgery, the air is exchanged for a long-lasting gas, which fills the central cavity of the eye and keeps the retina attached until a seal develops around the retinal breaks. The gas will slowly be reabsorbed by the eye, over a period of 2-8 weeks (depending on the choice of gas).

A scleral buckle may also be placed around the eye, to aid retinal reattachment in more complex cases.

Vitrectomy surgery is the most common method of retinal detachment repair. It is more comfortable for patients and causes fewer postoperative changes in the eye. It is particularly indicated when there is vitreous opacity (usually blood), when retinal breaks are difficult to treat with a scleral buckle (eg multiple breaks or ‘giant’ retinal breaks), and it is often used when there has been previous cataract surgery. It is required if surface retinal scarring (proliferative vitreoretinopathy {PVR} – which is the most frequent cause of failed retinal reattachment surgery) is present, so that the scar tissue can be peeled away from the retina.

Postoperative Recovery

Retinal reattachment surgery is major eye surgery. If intraocular gas is used to aid retinal reattachment, then you will need to position the head so that the gas rises within the eye to cover the retinal break. Posturing may be needed for up to 7 days. In general, most patients return to normal activities by 2 – 3 weeks after surgery.

Eye drops, including steroids, an antibiotic, and a cycloplegic (e.g. atropine or homatropine which relax the muscles within the eye) are continued during this period.

Outcome after Retinal Reattachment Surgery

Retinal reattachment is achieved after a single procedure in 80-90% of cases. It is important to remember that a second procedure may be required, and that in 4% of cases, the retina is unable to be reattached despite further surgery.

If the macula is uninvolved by the retinal detachment, approximately 90% of patients retain their preoperative level of vision. However, if the central macula is involved then the vision is never as good as it was, the average being 6/18 (or approximately half way down the reading chart).

Summary

- Retinal Detachment is a reasonably common and important cause of visual loss.

- Retinal Detachment develops after the formation of a retinal break (tear), which allows fluid from the vitreous cavity to enter the subretinal space, causing the retina to detach from its normal position.

- Posterior vitreous detachment causes the majority of retinal tears.

- The sudden onset of flashes, floaters, and peripheral visual field loss that progresses to loss of central vision requires same-day referral to an ophthalmologist.

- Treatment of retinal detachment requires surgery, which has a high rate of success.